The Mycenaeans

Mycenae was a Greek city-state that was the dominant power in the Ægean from ca. 1400 to 1100 BC. This bronze-age civilization found its power in its military, as did many states in archaic times. The concept of the heavy infantryman was not yet relevant, as mobility was a major factor in warfare.

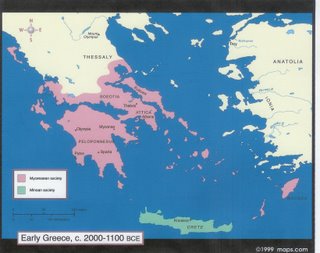

Mycenae was a Greek city-state that was the dominant power in the Ægean from ca. 1400 to 1100 BC. This bronze-age civilization found its power in its military, as did many states in archaic times. The concept of the heavy infantryman was not yet relevant, as mobility was a major factor in warfare.The Mycenaean state grew at a steady pace. The other city-states of the Peloponnesian Peninsula and mainland Greece were subdued in a fairly short time. Even the mighty Cretan civilization of Minos fell to her knees before the armies of Mycenae.

Unfortunately, the sources of information concerning the Mycenaean military are rather scarce. There was the major discovery of the actual citadel of Mycenae in 1841 and the more complete excavation in 1874 by Heinrich Schliemann, plus a few minor archaeological sites. Other than that, much of our knowledge of Mycenaean society derives from Homer. In the Iliad, he refers to the Greeks as Achaeans, Argives, and Danaans alternately. These may have been names of small Greek kingdoms, or they could have been different names for the Hellenes. Anyway, the Mycenaeans were best known for leading the armies for the armies of the Hellenic kingdoms against the city-state of Troy (known as Ilion or Troia to the Greeks, Illium to the Romans, and possibly Wilusa to the Hittites) in Asia Minor.

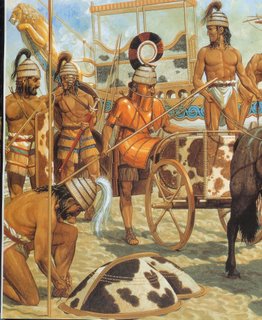

The Mycenaean soldier of the Trojan war would have been armed with a bronze-headed spear perhaps 2.5 metres in length, which probably would have been used for thrusting, but it could be thrown if the warrior so desired. His shield would be ox- or cowhide stretched over wicker, perhaps. Only nobility and charioteers (horseback riding was only used in the far east at this point) would wear armor of any kind, but most warriors would wear bronze swords as long as a metre, which was very irregular for weapons of this and the following period, suggesting that the Mycenaean blacksmith was particularly proficient in his art. The helm of this bronze-age warrior would have been constructed by its wearer, consisting of boar-tusk plates sewn on to a leather cap. A horsetail crest would have embellished the top.

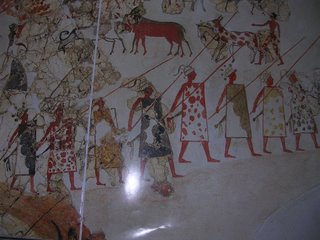

The order of battle would probably have been a large press of disorganized masses. The Mycenaean warrior would find it honorable to die amongst the corpses of his foes. Honor was also sought in single combat. Some historians doubt this theory, as it may have been an element borrowed from Homer's own time.

An excerpt from Fighting Techniques of the Ancient World by Simon Anglim, et al.:

There is no evidence to refute the Homeric notion of single combat between champions - the story of David and Goliath indicates that this was practised among the Sea Peoples, who were contemporary and culturally similar to the Mycenaeans. However, many historians argue this was more part of Homer's own time, the so-called Greek 'Dark Age'. Battles of this period were undisciplined mêlées in which the warrior ethic reigned supreme, with aristocrats and champions duelling for prestige.

Apparently, the Mycenaean civilization began to crumble as soon as barbaric tribes of northwestern Greeks* (today called the Dorians) invaded in huge hordes and set up their own civilization which lasted more or less until the Romans invaded, and even then, it remained greatly undisturbed until the establishment of the Crusader kingdoms and, later, the final invasion of the Ottoman Turks in the latter half of the fifteenth century.

*One of the Dorian tribes called itself the Ghrekos. The Italic peoples (later the Romans) knew of this tribe and mistakenly referred to all of Hellas as "Grecia".

Also, because of the Greek colonies on the Italian coast, the Italic tribes referred to eastern Italy as "Magna Grecia", or "Greater Greece", when it was, in fact, only a small colonization. Despite its innacuracy, this title stuck throughout Classical Times.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home