The Macedonian Army

[more to come]

A blog where we write about history. Mostly military history and some political history. We will give our own opinions. If you don't like it, too bad!!!!!!!!!!! However, we will also include pure, genuine fact. Feel free to comment. We will tell about some things in great detail. Some things we'll cover lightly, and there's a ton of stuff we just don't know. Tell us if we get anything wrong. Enjoy!!

Here is the master glossary:

An excerpt from Soldiers & Ghosts by J.E. Lendon:

An excerpt from Soldiers & Ghosts by J.E. Lendon:

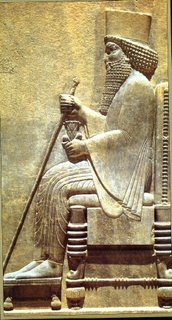

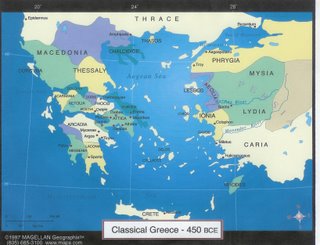

Between 612 and 615 BC, the mighty Assyrian Empire, long past its day of glory, was dissolved by the forces of an unknown King of the Medes. But the Medians were not as strong and ruthless as the Assyrians were to become so powerful. Less than a century later, an ambitious prince, Cyrus (Kuruš) by name, cast the crown of the Medes to the ground and proceeded to take the land of the Tigris and Euphrates by force. He called his kingdom Pārsā ("above reproach", according to Wikipedia), or Persis to Hellenic ears. The kings that came after him carried on his great legacy a hundred fold, stretching the Persian Empire [below] from Egypt and Thrace all the way to India at the time of the reign of Darius I (Dārayawuš) the Great [above, right]. These Persians were certainly not as cruelly heavy-handed as the Assyrians were, but they had a healthy love of war and an intense enjoyment for enjoying its spoils. No Persian King could resist the feeling of a once-great nation groveling at his feet.

Between 612 and 615 BC, the mighty Assyrian Empire, long past its day of glory, was dissolved by the forces of an unknown King of the Medes. But the Medians were not as strong and ruthless as the Assyrians were to become so powerful. Less than a century later, an ambitious prince, Cyrus (Kuruš) by name, cast the crown of the Medes to the ground and proceeded to take the land of the Tigris and Euphrates by force. He called his kingdom Pārsā ("above reproach", according to Wikipedia), or Persis to Hellenic ears. The kings that came after him carried on his great legacy a hundred fold, stretching the Persian Empire [below] from Egypt and Thrace all the way to India at the time of the reign of Darius I (Dārayawuš) the Great [above, right]. These Persians were certainly not as cruelly heavy-handed as the Assyrians were, but they had a healthy love of war and an intense enjoyment for enjoying its spoils. No Persian King could resist the feeling of a once-great nation groveling at his feet.

Knowledge of how the Persians organized their armed forces is rather shadowy compared to our colourful view of the Greeks. This is because the ancient writers tended to romanticize the Greeks and to portray the Persian armies as immense, squabbling masses of a million soldiers, miraculously overcome by a small ragtag group of Greeks. Not that the Greeks weren't awesome. Often 'twas the case when a great Persian army, outnumbering the Greek hoplites at least 3:1, was defeated. Indeed, in the case of Thermopylae, the odds were as much as perhaps 300:1 in Persian favour on the third day. This is not to say that the Persians were evil; every conquering nation is seen in a different light. Simply being the aggressors in the Græco-Persian War leads people to believe the Persians were in the wrong. The Greeks certainly weren't, but assessing accountability in war is a shady business. Although, I suppose that in those rather undiplomatic times, if you invaded a country and won, you were seen as the heroic victors removing a malicious power. If your forces were defeated by the locals defending their homeland, you were seen as a heartless invader overcome by simple men with tremendous loyalty. But the point is moot. In the Græco-Persian War, it is generally accepted that, while being a grand and sophisticated nation, the Persians were the bad guys.

Knowledge of how the Persians organized their armed forces is rather shadowy compared to our colourful view of the Greeks. This is because the ancient writers tended to romanticize the Greeks and to portray the Persian armies as immense, squabbling masses of a million soldiers, miraculously overcome by a small ragtag group of Greeks. Not that the Greeks weren't awesome. Often 'twas the case when a great Persian army, outnumbering the Greek hoplites at least 3:1, was defeated. Indeed, in the case of Thermopylae, the odds were as much as perhaps 300:1 in Persian favour on the third day. This is not to say that the Persians were evil; every conquering nation is seen in a different light. Simply being the aggressors in the Græco-Persian War leads people to believe the Persians were in the wrong. The Greeks certainly weren't, but assessing accountability in war is a shady business. Although, I suppose that in those rather undiplomatic times, if you invaded a country and won, you were seen as the heroic victors removing a malicious power. If your forces were defeated by the locals defending their homeland, you were seen as a heartless invader overcome by simple men with tremendous loyalty. But the point is moot. In the Græco-Persian War, it is generally accepted that, while being a grand and sophisticated nation, the Persians were the bad guys.

In all the years that man has fought against one another, there have been few if any armies with greater discipline than that of a Greek army. The standard heavy infantry of a contingent of Greeks and the very backbone of the army was the hoplite [right].

In all the years that man has fought against one another, there have been few if any armies with greater discipline than that of a Greek army. The standard heavy infantry of a contingent of Greeks and the very backbone of the army was the hoplite [right].  round, colorfully adorned shields with a large diameter of one metre. The earlier Mycenaean shields had taken many shapes, but almost all of the classical H e l l e n i c shields used by these shock troops were circular concave items with a pair of strips on the back that were meant for the hand and forearm. This wooden or bronze (usually both) shield was known as the aspis or hoplon. The name for the infantry, hoplite (hoplitēs, οπλίτης), can be taken to be derived from hoplon, which originally meant 'tool,' later 'tool of war.' Aspis is the general word for shield.

round, colorfully adorned shields with a large diameter of one metre. The earlier Mycenaean shields had taken many shapes, but almost all of the classical H e l l e n i c shields used by these shock troops were circular concave items with a pair of strips on the back that were meant for the hand and forearm. This wooden or bronze (usually both) shield was known as the aspis or hoplon. The name for the infantry, hoplite (hoplitēs, οπλίτης), can be taken to be derived from hoplon, which originally meant 'tool,' later 'tool of war.' Aspis is the general word for shield.

Greek swords were straight, double-edged affairs, stretching between sixty and seventy centimetres in length. Often the edges themselves were curved in such a way that the blade of the xiphos resembled an oblong leaf, hence the term 'leaf-bladed'. The specific model on the left is known as the 'lakonian' ('spartan'). It is an earlier iron type, later being replaced with the longer type [right]. Thie xiphos was not the only type of sword used by the Greeks. Two similar sword types were developed on the side: the machaira and the kopis [below], the later better known for the Iberian peoples' use of it against the Romans (there known as the falcata).

Greek swords were straight, double-edged affairs, stretching between sixty and seventy centimetres in length. Often the edges themselves were curved in such a way that the blade of the xiphos resembled an oblong leaf, hence the term 'leaf-bladed'. The specific model on the left is known as the 'lakonian' ('spartan'). It is an earlier iron type, later being replaced with the longer type [right]. Thie xiphos was not the only type of sword used by the Greeks. Two similar sword types were developed on the side: the machaira and the kopis [below], the later better known for the Iberian peoples' use of it against the Romans (there known as the falcata).  The whole idea of the kopis is, in my humble opinion, the long blade and easy wielding of the sword blended with the momentum- fetching, bone- crushing, pig- headedness of the axe. This sword was favored more in the later centuries of hellenic warfare, particularly in the case of the Macedonians under Philip II and Alexander III. Perhaps the design was given to the Iberians by Greek colonists, for the pattern is exactly the same, apart from the Greek style being slightly longer and more slender. As for the machaira, it is exactly the same but without a pommel and no guard for the lower hand.

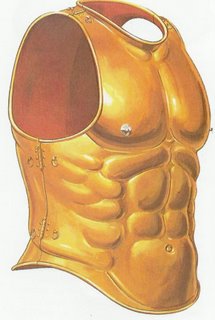

The whole idea of the kopis is, in my humble opinion, the long blade and easy wielding of the sword blended with the momentum- fetching, bone- crushing, pig- headedness of the axe. This sword was favored more in the later centuries of hellenic warfare, particularly in the case of the Macedonians under Philip II and Alexander III. Perhaps the design was given to the Iberians by Greek colonists, for the pattern is exactly the same, apart from the Greek style being slightly longer and more slender. As for the machaira, it is exactly the same but without a pommel and no guard for the lower hand. cuirass [left] was the norm. This 'bell cuirass', as it was called, was rather heavy, and, according to Victor David Hanson, hoplites preferred to wait until seconds before engagement to actually don the armour. The bell cuirass enjoyed extreme popularity until the sixth century BC, when it became increasingly ornate and was very expensive to produce. This newer version is perhaps the best known

cuirass [left] was the norm. This 'bell cuirass', as it was called, was rather heavy, and, according to Victor David Hanson, hoplites preferred to wait until seconds before engagement to actually don the armour. The bell cuirass enjoyed extreme popularity until the sixth century BC, when it became increasingly ornate and was very expensive to produce. This newer version is perhaps the best known  type of Greek armour for its later use by officers and patricians in the Roman Empire. It is simply called the 'muscled cuirass' [right]. The earlier bronze ones were obviously more decorated than the iron ones, as bronze is a much easier metal to work with. Nevertheless, the muscled cuirass pattern was used throughout antiquity, if only in small numbers. The muscled cuirass pictured on the right is a reconstruction of the full-length version. Some were slightly shorter to allow greater movement of the waist. These short cuirasses were the ones later used by Roman officials. Another way the muscled cuirass was modified for more comfort was to simply enlarge the arm openings and to spread the bottom half out on all sides, like a more exaggerated bell cuirass. This wide type was used exclusively by horsemen so that they could fit on a

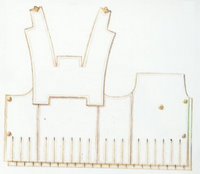

type of Greek armour for its later use by officers and patricians in the Roman Empire. It is simply called the 'muscled cuirass' [right]. The earlier bronze ones were obviously more decorated than the iron ones, as bronze is a much easier metal to work with. Nevertheless, the muscled cuirass pattern was used throughout antiquity, if only in small numbers. The muscled cuirass pictured on the right is a reconstruction of the full-length version. Some were slightly shorter to allow greater movement of the waist. These short cuirasses were the ones later used by Roman officials. Another way the muscled cuirass was modified for more comfort was to simply enlarge the arm openings and to spread the bottom half out on all sides, like a more exaggerated bell cuirass. This wide type was used exclusively by horsemen so that they could fit on a  horse. The last cuirass is called the 'linothrax', or linen cuirass. The linen cuirass was constructed of a pair of thick, stiff linen shapes in the pattern on the left with the shoulder straps attached on the back. The linothrax was usually decorated with Greek 'keys', or geometric patterns in on or two colors. Some featured the common Greek stylized gorgon head. It may seem too light and just downright weak, but the linen cuirass enjoyed a huge amount of popularity according to classical vases and such. Therefore, it must have been effective in some way. Peter Connolly claims to have made his own, but it is also available from websites such as Manning Imperial for a rather large amount of Australian dollars.

horse. The last cuirass is called the 'linothrax', or linen cuirass. The linen cuirass was constructed of a pair of thick, stiff linen shapes in the pattern on the left with the shoulder straps attached on the back. The linothrax was usually decorated with Greek 'keys', or geometric patterns in on or two colors. Some featured the common Greek stylized gorgon head. It may seem too light and just downright weak, but the linen cuirass enjoyed a huge amount of popularity according to classical vases and such. Therefore, it must have been effective in some way. Peter Connolly claims to have made his own, but it is also available from websites such as Manning Imperial for a rather large amount of Australian dollars.

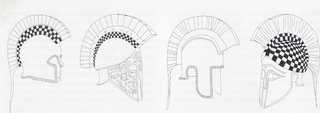

helmet is a late Corinthan helm. The ear holes are a sure giveaway that a helmet is from the later period of Greek warfare. Bronze was the chosen metal to mould into intricate items like these helmets. Copper had been obsolete for many centuries, and iron was too hard. The happy medium was bronze, which was very easy to bend into elegant greaves and formidable helms. The crests were of horse hair (presumably taken from the tail) and dyed red, white, or simply left black. Generally, the crests faced

helmet is a late Corinthan helm. The ear holes are a sure giveaway that a helmet is from the later period of Greek warfare. Bronze was the chosen metal to mould into intricate items like these helmets. Copper had been obsolete for many centuries, and iron was too hard. The happy medium was bronze, which was very easy to bend into elegant greaves and formidable helms. The crests were of horse hair (presumably taken from the tail) and dyed red, white, or simply left black. Generally, the crests faced forward and back like the one pictures, but kings and officers preferred to wear the transverse crest [right] as a symbol of rank.

forward and back like the one pictures, but kings and officers preferred to wear the transverse crest [right] as a symbol of rank. The Peltast

The Peltast

Marathon: 490 B.C.

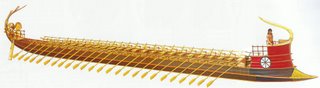

One of the greatest victories in history occurred when a Greek force of 10,400 stopped a Persian invasion of 20,000 men and horse. King Darius I of Persia and Athens had for many years been at a standstill caused by the Persian's conquest of Greek Ionia (what is now western Turkey). In 499 B.C. the Ionians revolted as they were joined by a force of 25 triremes from Athens. Soon thereafter, Darius I crushed this revolt (494 B.C.) and decided to attack the Greeks at the first opportunity. Darius then appointed Datis, Mede and his nephew Artaphrenes to gather an army (600 triremes worth) which they soon achieved and quickly crushed once again any Greek resistance in Ionia (Eretria). After this victory they turned the fleet to the west towards Athens. The Athenians marched on Marathon (a nearby village) where the Persians had landed their gargantuan army. The Greek commanders voted on whether to attack or retreat until Spartan forces arrived. A commander by the name of Callimachus was forced to make the final decision. He decided for open conflict, not a cowardly flight.

There is a Spartan saying that goes thus: 'Come home with this shield or upon it.' as a Spartan is handed his shield by his mother. This aphorism shows the importance of bravery. When fleeing a battle, the first thing a warrior would do would be to cast aside his shield which could weigh several kilograms. If that warrior was killed in battle his body was returned to his mother on his shield. This shows just how militaristic and firm the Spartan society was. Because of this they were the best warriors in the world for several hundred years, a feat that no other force has ever rightfully claimed. The only individuals with a chance of defeating a Spartan were members of the Theban Sacred Band or an Athenian Myrmidon. As has been discussed in previous posts, honour was a virtue that every Greek abided by and for one polis (city state) to retreat from battle would cause an undue amount of shame for years—nay, centuries to come.

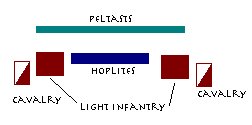

When the battle commenced, the Athenians charged their Persian adversaries. The Athenian phalanx was strongest on the flanks, thus as the two sides clashed, the Athenian centre began to collapse. At this time Athenian peltasts began to rain barrages of missile fire into the Persians, now held in place by the Athenian heavy infantry. Soon the Persian flanks began to collapse due to the additional Athenian troop strength but the Athenian centre began to weaken. The Persian spearmen managed to puncture the middle of the Athenian line, but by this time it was too late. The archers on the Persian flanks fought with their falchions but were literally rolled over by the heavily armed Greeks. The Athenians managed to bring their wings around to meet at the back of the mass of Persians, at which point the invaders saw their folly and broke. Thousands were slaughtered there as they tried to run past the fury of the Hellenes and back to their beached ships, some of which were already burning. Somewhere near 6400 Persians fell on that field outside of Athens, while the defenders boasted a miraculously small 192 casualties. The Asians also lost a few ships to the Athenians in their panic.

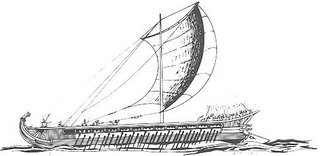

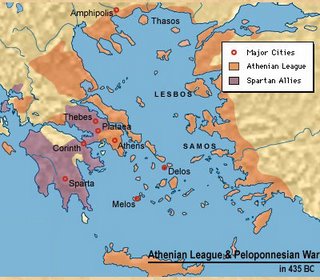

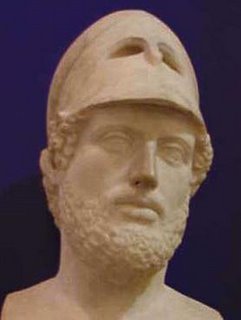

Athenians were diplomatically, socially and territorially superior enough to be called an empire. Their holdings were spread around the Aegean Sea, from Attica and Thessaly on the Greek mainland to the numerous cities scattered across the west coast of Asia Minor, and all of the hundreds of islands in between. Their allies stood close and firm, and a new, strong leader was at their head: Pericles. The people of Athens had great confidence in him (obviously, since the elected him), and followed his orders without question. He held in his hand the unquestionable might of Athenian money and naval prowess.

Athenians were diplomatically, socially and territorially superior enough to be called an empire. Their holdings were spread around the Aegean Sea, from Attica and Thessaly on the Greek mainland to the numerous cities scattered across the west coast of Asia Minor, and all of the hundreds of islands in between. Their allies stood close and firm, and a new, strong leader was at their head: Pericles. The people of Athens had great confidence in him (obviously, since the elected him), and followed his orders without question. He held in his hand the unquestionable might of Athenian money and naval prowess. In the year 433 before the birth of Christ, Athens had her eyes set on higher prizes than those she had already obtained. Pericles may have well known the risk he was taking in consorting with a colony of Corinth, but he had faith in the power he had around him. He took the brazen step of forming an alliance between his own city-state and the Corinthian island colony of Corcyra in the Ionian Sea. Corinth was deeply offended because of their deep-rooted bias against the Athenians, and demanded that the alliance be dissolved. Pericles, angered by this gross disregard of Athenian authority, declared a complete trade embargo with the city of Corinth. Being the head of the Peloponnesian network of alliances, everyone looked to the Spartans to act. With the fell smack of the proverbial gavel, Sparta declared war on Athens in 431 BC.

In the year 433 before the birth of Christ, Athens had her eyes set on higher prizes than those she had already obtained. Pericles may have well known the risk he was taking in consorting with a colony of Corinth, but he had faith in the power he had around him. He took the brazen step of forming an alliance between his own city-state and the Corinthian island colony of Corcyra in the Ionian Sea. Corinth was deeply offended because of their deep-rooted bias against the Athenians, and demanded that the alliance be dissolved. Pericles, angered by this gross disregard of Athenian authority, declared a complete trade embargo with the city of Corinth. Being the head of the Peloponnesian network of alliances, everyone looked to the Spartans to act. With the fell smack of the proverbial gavel, Sparta declared war on Athens in 431 BC. “pestilence”, as they called it. Realizing that decisive action must be taken, Pericles proceeded to take his navy form the port of Piraeus and attempted to capture the Spartan-loyal city of Epidaurus. In this he failed, but his navy ravished the eastern coastline of the Peloponnesus all the same. Hoping to be greeted with more respect upon his arrival to Athens, he was greatly disappointed and surprised. The Spartan army had been rampaging around Attica for forty days, pillaging and killing, all the while keeping Athens herself under siege. On his return, he was kicked out of office. Seeing their mistake soon after, he was reelected and he continued his rule. But he only ruled for one more year, for the plague continued, and it ensnared Pericles in the end. He died within only within a few years of the War’s opening.

“pestilence”, as they called it. Realizing that decisive action must be taken, Pericles proceeded to take his navy form the port of Piraeus and attempted to capture the Spartan-loyal city of Epidaurus. In this he failed, but his navy ravished the eastern coastline of the Peloponnesus all the same. Hoping to be greeted with more respect upon his arrival to Athens, he was greatly disappointed and surprised. The Spartan army had been rampaging around Attica for forty days, pillaging and killing, all the while keeping Athens herself under siege. On his return, he was kicked out of office. Seeing their mistake soon after, he was reelected and he continued his rule. But he only ruled for one more year, for the plague continued, and it ensnared Pericles in the end. He died within only within a few years of the War’s opening. The Spartan Alliance was supplied by the Corinthians, who ruled the city of Syracuse on Sicily. Syracuse was so rich in resources that if the Corinthians lost contact with it, their supplies would be depleted and they would have to surrender. A massive force of Athenians gathered at the port of Piraeus and sailed off to Syracuse with Nicias, Alcibiades and a general named Lamachus. The “Sicilian Expedition”, as it came to be called in later years, was perhaps the worst yet most predictable mistake that the Athenians could have made. Alcibiades could have saved the expedition, but upon arrival at Sicily, news reached him that he was to stand trial in Athens for blasphemy of images of Hermes. He more or less freaked out and switched to the Spartan side.

The Spartan Alliance was supplied by the Corinthians, who ruled the city of Syracuse on Sicily. Syracuse was so rich in resources that if the Corinthians lost contact with it, their supplies would be depleted and they would have to surrender. A massive force of Athenians gathered at the port of Piraeus and sailed off to Syracuse with Nicias, Alcibiades and a general named Lamachus. The “Sicilian Expedition”, as it came to be called in later years, was perhaps the worst yet most predictable mistake that the Athenians could have made. Alcibiades could have saved the expedition, but upon arrival at Sicily, news reached him that he was to stand trial in Athens for blasphemy of images of Hermes. He more or less freaked out and switched to the Spartan side.

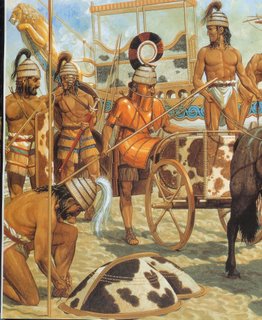

Mycenae was a Greek city-state that was the dominant power in the Ægean from ca. 1400 to 1100 BC. This bronze-age civilization found its power in its military, as did many states in archaic times. The concept of the heavy infantryman was not yet relevant, as mobility was a major factor in warfare.

Mycenae was a Greek city-state that was the dominant power in the Ægean from ca. 1400 to 1100 BC. This bronze-age civilization found its power in its military, as did many states in archaic times. The concept of the heavy infantryman was not yet relevant, as mobility was a major factor in warfare.