The Greek Army

In all the years that man has fought against one another, there have been few if any armies with greater discipline than that of a Greek army. The standard heavy infantry of a contingent of Greeks and the very backbone of the army was the hoplite [right].

In all the years that man has fought against one another, there have been few if any armies with greater discipline than that of a Greek army. The standard heavy infantry of a contingent of Greeks and the very backbone of the army was the hoplite [right]. In Erich Maria Remarque's Im Westen nichts Neues, a character by the name of Albert Kropp wonders why the opposing leaders don't just duke it out themselves rather than spend the lives of hundreds of thousands of the wrong people. It is similar nowadays, where the poor turn to the army because it is the only thing that they can do, and fight the war for the rich people who have things to lose. Back in the day (classical times), war was a much more serious affair for the rich. First of all, usually only the rich could go to was because only they had the money for equipment. Instead of the aristocrats thrusting less fortunate citizens in as a shield, the rich and upper middle class set out to fight for their land and people. This didn't change in the Mediterranean until 107 BC, when Consul Gaius Marius pushed for a great number of reforms in the Roman army, which included that weapons and equipment be provided by the state, thus allowing the poor to enlist by the thousands. We'll tell you more about it in the Roman section.

The Hoplite

In spite of the rich being the endangered, war flourished in the Ægean between 750 and 200 BC. The chosen type of soldier for the ancient Greeks was a heavily armed mêlée infantryman. When a company of Hellenes came marching, the most immediately noticeable things were the

round, colorfully adorned shields with a large diameter of one metre. The earlier Mycenaean shields had taken many shapes, but almost all of the classical H e l l e n i c shields used by these shock troops were circular concave items with a pair of strips on the back that were meant for the hand and forearm. This wooden or bronze (usually both) shield was known as the aspis or hoplon. The name for the infantry, hoplite (hoplitēs, οπλίτης), can be taken to be derived from hoplon, which originally meant 'tool,' later 'tool of war.' Aspis is the general word for shield.

round, colorfully adorned shields with a large diameter of one metre. The earlier Mycenaean shields had taken many shapes, but almost all of the classical H e l l e n i c shields used by these shock troops were circular concave items with a pair of strips on the back that were meant for the hand and forearm. This wooden or bronze (usually both) shield was known as the aspis or hoplon. The name for the infantry, hoplite (hoplitēs, οπλίτης), can be taken to be derived from hoplon, which originally meant 'tool,' later 'tool of war.' Aspis is the general word for shield.Spear

There is little to be said for the spear. It was not very long at about 2-2.5 metres, and was used exclusively for thrusting. Until the phenomenon of the Boetian (Dipylon) shield, the spear was wielded overhand, as if one were to throw it. The head itself was iron and plainly leaf shaped, not barbed or with a crossguard. The haft was ash, and the butt-spike was bronze rather than iron; it was also an actual spike, unlike the earlier apple-shaped Persian ones.

Sword

The sword comes next. Many books seem to resist using the word xiphos (indeed, the only term in Greek for the word 'spear' that we have found is 'dory'), but it is the best that we have, so we'll use it. Most

Greek swords were straight, double-edged affairs, stretching between sixty and seventy centimetres in length. Often the edges themselves were curved in such a way that the blade of the xiphos resembled an oblong leaf, hence the term 'leaf-bladed'. The specific model on the left is known as the 'lakonian' ('spartan'). It is an earlier iron type, later being replaced with the longer type [right]. Thie xiphos was not the only type of sword used by the Greeks. Two similar sword types were developed on the side: the machaira and the kopis [below], the later better known for the Iberian peoples' use of it against the Romans (there known as the falcata).

Greek swords were straight, double-edged affairs, stretching between sixty and seventy centimetres in length. Often the edges themselves were curved in such a way that the blade of the xiphos resembled an oblong leaf, hence the term 'leaf-bladed'. The specific model on the left is known as the 'lakonian' ('spartan'). It is an earlier iron type, later being replaced with the longer type [right]. Thie xiphos was not the only type of sword used by the Greeks. Two similar sword types were developed on the side: the machaira and the kopis [below], the later better known for the Iberian peoples' use of it against the Romans (there known as the falcata).  The whole idea of the kopis is, in my humble opinion, the long blade and easy wielding of the sword blended with the momentum- fetching, bone- crushing, pig- headedness of the axe. This sword was favored more in the later centuries of hellenic warfare, particularly in the case of the Macedonians under Philip II and Alexander III. Perhaps the design was given to the Iberians by Greek colonists, for the pattern is exactly the same, apart from the Greek style being slightly longer and more slender. As for the machaira, it is exactly the same but without a pommel and no guard for the lower hand.

The whole idea of the kopis is, in my humble opinion, the long blade and easy wielding of the sword blended with the momentum- fetching, bone- crushing, pig- headedness of the axe. This sword was favored more in the later centuries of hellenic warfare, particularly in the case of the Macedonians under Philip II and Alexander III. Perhaps the design was given to the Iberians by Greek colonists, for the pattern is exactly the same, apart from the Greek style being slightly longer and more slender. As for the machaira, it is exactly the same but without a pommel and no guard for the lower hand.Armour and Helmet

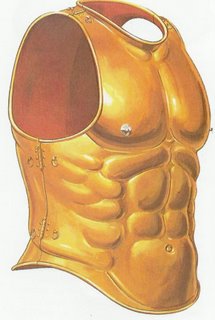

The armor varies greatly depending on the specific era. In the early time of the heavy hoplite around 700 BC (not long after the 'champion' type of combat had been abolished), a simple bronze

cuirass [left] was the norm. This 'bell cuirass', as it was called, was rather heavy, and, according to Victor David Hanson, hoplites preferred to wait until seconds before engagement to actually don the armour. The bell cuirass enjoyed extreme popularity until the sixth century BC, when it became increasingly ornate and was very expensive to produce. This newer version is perhaps the best known

cuirass [left] was the norm. This 'bell cuirass', as it was called, was rather heavy, and, according to Victor David Hanson, hoplites preferred to wait until seconds before engagement to actually don the armour. The bell cuirass enjoyed extreme popularity until the sixth century BC, when it became increasingly ornate and was very expensive to produce. This newer version is perhaps the best known  type of Greek armour for its later use by officers and patricians in the Roman Empire. It is simply called the 'muscled cuirass' [right]. The earlier bronze ones were obviously more decorated than the iron ones, as bronze is a much easier metal to work with. Nevertheless, the muscled cuirass pattern was used throughout antiquity, if only in small numbers. The muscled cuirass pictured on the right is a reconstruction of the full-length version. Some were slightly shorter to allow greater movement of the waist. These short cuirasses were the ones later used by Roman officials. Another way the muscled cuirass was modified for more comfort was to simply enlarge the arm openings and to spread the bottom half out on all sides, like a more exaggerated bell cuirass. This wide type was used exclusively by horsemen so that they could fit on a

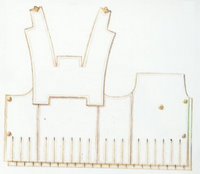

type of Greek armour for its later use by officers and patricians in the Roman Empire. It is simply called the 'muscled cuirass' [right]. The earlier bronze ones were obviously more decorated than the iron ones, as bronze is a much easier metal to work with. Nevertheless, the muscled cuirass pattern was used throughout antiquity, if only in small numbers. The muscled cuirass pictured on the right is a reconstruction of the full-length version. Some were slightly shorter to allow greater movement of the waist. These short cuirasses were the ones later used by Roman officials. Another way the muscled cuirass was modified for more comfort was to simply enlarge the arm openings and to spread the bottom half out on all sides, like a more exaggerated bell cuirass. This wide type was used exclusively by horsemen so that they could fit on a  horse. The last cuirass is called the 'linothrax', or linen cuirass. The linen cuirass was constructed of a pair of thick, stiff linen shapes in the pattern on the left with the shoulder straps attached on the back. The linothrax was usually decorated with Greek 'keys', or geometric patterns in on or two colors. Some featured the common Greek stylized gorgon head. It may seem too light and just downright weak, but the linen cuirass enjoyed a huge amount of popularity according to classical vases and such. Therefore, it must have been effective in some way. Peter Connolly claims to have made his own, but it is also available from websites such as Manning Imperial for a rather large amount of Australian dollars.

horse. The last cuirass is called the 'linothrax', or linen cuirass. The linen cuirass was constructed of a pair of thick, stiff linen shapes in the pattern on the left with the shoulder straps attached on the back. The linothrax was usually decorated with Greek 'keys', or geometric patterns in on or two colors. Some featured the common Greek stylized gorgon head. It may seem too light and just downright weak, but the linen cuirass enjoyed a huge amount of popularity according to classical vases and such. Therefore, it must have been effective in some way. Peter Connolly claims to have made his own, but it is also available from websites such as Manning Imperial for a rather large amount of Australian dollars.

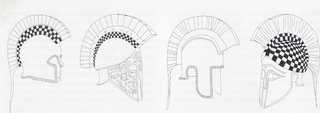

Now for the helmets. In the picture on the right, the far left helmet is a very early Corinthian helmet. Corinthan helms are identified easily by covering most of the face and having a nose guards. Next is a heavily decorated Corinthian, and then the less common Illyrian helm, which has a squarish face and the noticably absent nose guard. These are obviously named for the Illyrians, a 'barbaric' people that resided in the Albania/Former Yugoslavia region. The last

helmet is a late Corinthan helm. The ear holes are a sure giveaway that a helmet is from the later period of Greek warfare. Bronze was the chosen metal to mould into intricate items like these helmets. Copper had been obsolete for many centuries, and iron was too hard. The happy medium was bronze, which was very easy to bend into elegant greaves and formidable helms. The crests were of horse hair (presumably taken from the tail) and dyed red, white, or simply left black. Generally, the crests faced

helmet is a late Corinthan helm. The ear holes are a sure giveaway that a helmet is from the later period of Greek warfare. Bronze was the chosen metal to mould into intricate items like these helmets. Copper had been obsolete for many centuries, and iron was too hard. The happy medium was bronze, which was very easy to bend into elegant greaves and formidable helms. The crests were of horse hair (presumably taken from the tail) and dyed red, white, or simply left black. Generally, the crests faced forward and back like the one pictures, but kings and officers preferred to wear the transverse crest [right] as a symbol of rank.

forward and back like the one pictures, but kings and officers preferred to wear the transverse crest [right] as a symbol of rank. The Peltast

The PeltastThe peltast was a type of light, skirmisher infantry, equivalent to the Roman velite and the Irish kern. They were primarily used to harass the enemy and engage their equals on the opposing side. Their name, 'peltast', refers to the crescent-shaped shield that they often carried: the pelta. We have much less to say about them than the hoplite, as they were much less important. They were also known for their wearing of the 'Phrygian cap'.

Javelins

...were relatively standard with slight fluxuations according to the personal preferance of the wielder. That's all we know.

Shield

As was previously mentioned, peltasts bore the pelta, which resembled a cookie with a large bite out of it. It was constructed of wicker and then covered in leather or, rarely, bronze.

Cavalry

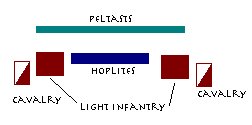

Greek Cavalry played a relatively insignificant role in battle. Primarily they were used as scouts and messengers. Almost all were very lightly armoured and armed with a sword or spear. This later became part of the cause of the fall of Greece and the rise of Macedon. Because of their armament, the cavalry was ineffictive as shock troops though were sometimes used in flanking an enemy. Below is a relatively standard formation of a Greek army with light infantry [in this case they were of a social lower class and carried only spear, sword, axe or anything that was on hand as they marched to war] and cavalry on the wings that will flank the enemy as they are held in place by the hoplites and harassed by the peltasts.

1 Comments:

Hi there love the subject and great work by the way. can I ask do you know who made the helmet in the picture with the black horse hair crossed crest ?

I love the design.

Post a Comment

<< Home