The Greek City-States

City States:

Ancient Greek society was based largly around the city state, or polis. The city, such as Athens, Sparta, and Pylos would hold dominance over the land surrounding it. Subsequently, they farmed, mined, and levied taxes from those inhabiting the province. Though each city was independant, each would form loose confederations with nearby cities or else gain dominance by force. Even after a city fell, it was largely left free. Normally it was only a single leader who paid the price of defeat. There have been numerous recordings of a son of the overthrown established on the throne by the victor to rule under certian ordinances increasing trade and fealty to the victor. {Not Finished}

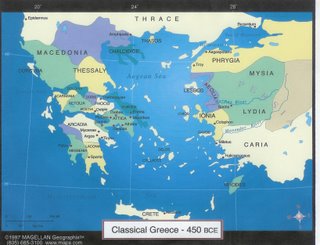

Classical Greece:

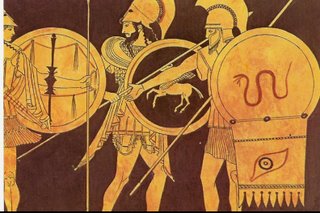

Earlier hoplites engaged other infantry in a simple shield wall formation with their hoplons presented forth and their spears held overhand. Later in the life of the Greek military, perhaps around the sixth century BC, a new formation was introduced: the phalanx ("roller"). Strictly speaking, the phalanx was not a new idea. It was in fact borrowed form the armies of the Mesopotamian area from around 2000 years earlier. Carvings form this time indicate that early agricultural realms such as Babylon, Lagash and Ur used soldiers similar to hoplites and deployed them in tightly-packed rectangular formations with soldiers in the further ranks form the front sticking their pikes out from behind the shields of the front rank and the ranks before them doing likewise. Sometimes shields were not used, but rather the spears wielded with both hands. This was very rare after Mesopotamian times until the 1400s, where it was widely used until the 1700s.

Marathon: 490 B.C.

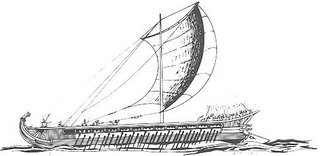

One of the greatest victories in history occurred when a Greek force of 10,400 stopped a Persian invasion of 20,000 men and horse. King Darius I of Persia and Athens had for many years been at a standstill caused by the Persian's conquest of Greek Ionia (what is now western Turkey). In 499 B.C. the Ionians revolted as they were joined by a force of 25 triremes from Athens. Soon thereafter, Darius I crushed this revolt (494 B.C.) and decided to attack the Greeks at the first opportunity. Darius then appointed Datis, Mede and his nephew Artaphrenes to gather an army (600 triremes worth) which they soon achieved and quickly crushed once again any Greek resistance in Ionia (Eretria). After this victory they turned the fleet to the west towards Athens. The Athenians marched on Marathon (a nearby village) where the Persians had landed their gargantuan army. The Greek commanders voted on whether to attack or retreat until Spartan forces arrived. A commander by the name of Callimachus was forced to make the final decision. He decided for open conflict, not a cowardly flight.

There is a Spartan saying that goes thus: 'Come home with this shield or upon it.' as a Spartan is handed his shield by his mother. This aphorism shows the importance of bravery. When fleeing a battle, the first thing a warrior would do would be to cast aside his shield which could weigh several kilograms. If that warrior was killed in battle his body was returned to his mother on his shield. This shows just how militaristic and firm the Spartan society was. Because of this they were the best warriors in the world for several hundred years, a feat that no other force has ever rightfully claimed. The only individuals with a chance of defeating a Spartan were members of the Theban Sacred Band or an Athenian Myrmidon. As has been discussed in previous posts, honour was a virtue that every Greek abided by and for one polis (city state) to retreat from battle would cause an undue amount of shame for years—nay, centuries to come.

When the battle commenced, the Athenians charged their Persian adversaries. The Athenian phalanx was strongest on the flanks, thus as the two sides clashed, the Athenian centre began to collapse. At this time Athenian peltasts began to rain barrages of missile fire into the Persians, now held in place by the Athenian heavy infantry. Soon the Persian flanks began to collapse due to the additional Athenian troop strength but the Athenian centre began to weaken. The Persian spearmen managed to puncture the middle of the Athenian line, but by this time it was too late. The archers on the Persian flanks fought with their falchions but were literally rolled over by the heavily armed Greeks. The Athenians managed to bring their wings around to meet at the back of the mass of Persians, at which point the invaders saw their folly and broke. Thousands were slaughtered there as they tried to run past the fury of the Hellenes and back to their beached ships, some of which were already burning. Somewhere near 6400 Persians fell on that field outside of Athens, while the defenders boasted a miraculously small 192 casualties. The Asians also lost a few ships to the Athenians in their panic.

The Peloponnesian War

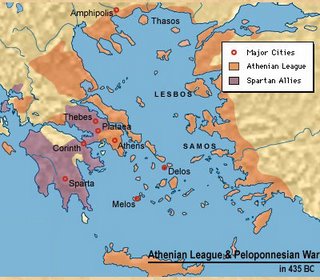

The Peloponnesian War began when the civilization of the Greek peoples was at its zenith. The

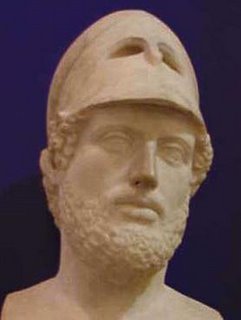

Athenians were diplomatically, socially and territorially superior enough to be called an empire. Their holdings were spread around the Aegean Sea, from Attica and Thessaly on the Greek mainland to the numerous cities scattered across the west coast of Asia Minor, and all of the hundreds of islands in between. Their allies stood close and firm, and a new, strong leader was at their head: Pericles. The people of Athens had great confidence in him (obviously, since the elected him), and followed his orders without question. He held in his hand the unquestionable might of Athenian money and naval prowess.

Athenians were diplomatically, socially and territorially superior enough to be called an empire. Their holdings were spread around the Aegean Sea, from Attica and Thessaly on the Greek mainland to the numerous cities scattered across the west coast of Asia Minor, and all of the hundreds of islands in between. Their allies stood close and firm, and a new, strong leader was at their head: Pericles. The people of Athens had great confidence in him (obviously, since the elected him), and followed his orders without question. He held in his hand the unquestionable might of Athenian money and naval prowess.The Spartans, by stark contrast, were conservative and military to the extreme; one might even call their system fascist. They were ruled as they had always been ruled: by one king descended from the king before him. Fighting was their life. From the day they could lift a sword to the day they were struck down by one, the Spartans trained to fight. They spent every waking hour preparing themselves for their next armed (or unarmed) struggle. Their army was the greatest the world had ever seen. Their solemnly steadfast allies included Corinth, Megara, and all others in the Peloponnesian Peninsula but Argos.

In the year 433 before the birth of Christ, Athens had her eyes set on higher prizes than those she had already obtained. Pericles may have well known the risk he was taking in consorting with a colony of Corinth, but he had faith in the power he had around him. He took the brazen step of forming an alliance between his own city-state and the Corinthian island colony of Corcyra in the Ionian Sea. Corinth was deeply offended because of their deep-rooted bias against the Athenians, and demanded that the alliance be dissolved. Pericles, angered by this gross disregard of Athenian authority, declared a complete trade embargo with the city of Corinth. Being the head of the Peloponnesian network of alliances, everyone looked to the Spartans to act. With the fell smack of the proverbial gavel, Sparta declared war on Athens in 431 BC.

In the year 433 before the birth of Christ, Athens had her eyes set on higher prizes than those she had already obtained. Pericles may have well known the risk he was taking in consorting with a colony of Corinth, but he had faith in the power he had around him. He took the brazen step of forming an alliance between his own city-state and the Corinthian island colony of Corcyra in the Ionian Sea. Corinth was deeply offended because of their deep-rooted bias against the Athenians, and demanded that the alliance be dissolved. Pericles, angered by this gross disregard of Athenian authority, declared a complete trade embargo with the city of Corinth. Being the head of the Peloponnesian network of alliances, everyone looked to the Spartans to act. With the fell smack of the proverbial gavel, Sparta declared war on Athens in 431 BC.The Athenian strategy was based around the simple idea that if they all left their fields and sat behind their stone walls, the Spartans would come, burn some countryside, throw a few stones, and eventually run out of resources and sue for peace. The Spartans thought to do nothing more than that, but with the besieging of several cities along the way. Thus began the great chain of devastating disasters that would lead the Athenian people to fall from their golden pedestal forever. All of the countrymen and farmers that lived on Athenian property called themselves Athenians and were allowed to vote as Athenians. All of these villagers and peasants were packed behind the strong walls of the city of Athens itself. With so very many people in such tight proximity to each other, any small event could affect a great many humans. It was never known where it came from, but a plague began in the densely populated urban center, possibly a strain of typhus. Bodies of the dead and dying could be found on every street of the sick city. No one was safe, and no one cared now about the Spartans.

In the political center of Athens, the politicians and aristocrats blamed Pericles for this

“pestilence”, as they called it. Realizing that decisive action must be taken, Pericles proceeded to take his navy form the port of Piraeus and attempted to capture the Spartan-loyal city of Epidaurus. In this he failed, but his navy ravished the eastern coastline of the Peloponnesus all the same. Hoping to be greeted with more respect upon his arrival to Athens, he was greatly disappointed and surprised. The Spartan army had been rampaging around Attica for forty days, pillaging and killing, all the while keeping Athens herself under siege. On his return, he was kicked out of office. Seeing their mistake soon after, he was reelected and he continued his rule. But he only ruled for one more year, for the plague continued, and it ensnared Pericles in the end. He died within only within a few years of the War’s opening.

“pestilence”, as they called it. Realizing that decisive action must be taken, Pericles proceeded to take his navy form the port of Piraeus and attempted to capture the Spartan-loyal city of Epidaurus. In this he failed, but his navy ravished the eastern coastline of the Peloponnesus all the same. Hoping to be greeted with more respect upon his arrival to Athens, he was greatly disappointed and surprised. The Spartan army had been rampaging around Attica for forty days, pillaging and killing, all the while keeping Athens herself under siege. On his return, he was kicked out of office. Seeing their mistake soon after, he was reelected and he continued his rule. But he only ruled for one more year, for the plague continued, and it ensnared Pericles in the end. He died within only within a few years of the War’s opening.After Pericles’ death, there were two men vying for power in the Athenian government. There was Nicias, a devout advocate of peace with Sparta, and Cleon, a hardened warrior, not unlike a Spartan himself. Nicias and Cleon more or less jointly shared the office of Ruler of Athens, but that was the only unifying quality that they had. Otherwise, their policies were very different, and kept the people split sharply into two factions of support.

The first great test as to who the Assembly (the Athenian legislative body made up of ordinary citizens) would back was in 428 BC, when the city of Mytilene on the island of Lesbos revolted against Athenian rule. Cleon proposed to send a ship full of soldiers over to Mytilene and massacre the entire population of men. Full of anger at the rebels, the Assembly agreed. Not so long after, however, they changed their minds and sent another ship that, with days of hard rowing, caught up with the first ship and told them to turn around.

Cleon was also very full of himself. At the Assembly, he boasted that he could sail around to the west side of the Peloponnesian Peninsula and take the city of Sphacteria, near the Spartan port Pylos. Nicias, in an attempt to deflate the headstrong Cleon, charged him to take the navy and do so. At everyone’s surprise, he succeeded. How much it did for the Athenians is unclear.

Lots of the Athenian people thought that it would be prudent to end the war here, when they were at an advantage. Cleon insisted on fighting though, and everything began to go downhill for the Athenians even faster than before. In 422 BC, at the Battle of Amphipolis in Thrace (northeast of Greece), Cleon himself fell in battle. A tentative peace treaty was signed in 421 BC, but all the Greeks knew that it meant nothing. In the absence of Cleon, Athens wanted a strong new leader unlike the timid Nicias. Young Alcibiades answered their call. He was a relative of Pericles, and the people accepted him with vigor. Alcibiades disregarded the Peace Treaty of 421 BC and began the assault on Sparta. He had a good plan, but there were certain problems that ended in complete tragedy for Athens.

The Spartan Alliance was supplied by the Corinthians, who ruled the city of Syracuse on Sicily. Syracuse was so rich in resources that if the Corinthians lost contact with it, their supplies would be depleted and they would have to surrender. A massive force of Athenians gathered at the port of Piraeus and sailed off to Syracuse with Nicias, Alcibiades and a general named Lamachus. The “Sicilian Expedition”, as it came to be called in later years, was perhaps the worst yet most predictable mistake that the Athenians could have made. Alcibiades could have saved the expedition, but upon arrival at Sicily, news reached him that he was to stand trial in Athens for blasphemy of images of Hermes. He more or less freaked out and switched to the Spartan side.

The Spartan Alliance was supplied by the Corinthians, who ruled the city of Syracuse on Sicily. Syracuse was so rich in resources that if the Corinthians lost contact with it, their supplies would be depleted and they would have to surrender. A massive force of Athenians gathered at the port of Piraeus and sailed off to Syracuse with Nicias, Alcibiades and a general named Lamachus. The “Sicilian Expedition”, as it came to be called in later years, was perhaps the worst yet most predictable mistake that the Athenians could have made. Alcibiades could have saved the expedition, but upon arrival at Sicily, news reached him that he was to stand trial in Athens for blasphemy of images of Hermes. He more or less freaked out and switched to the Spartan side.The attack began well, until Lamachus was killed. Now only Nicias was left. He requested reinforcements, who came just in time to replace the majority of the dead Athenians. Most of the new men died, however, and the rest wanted to return to Athens. Nicias, a very superstitious man, refused to leave when the moon was in eclipse, and the Sicilians caught up with them, killing some and enslaving many more. Only a few escaped.

Almost nothing remarkable occurred in in the last ten years of the war. Many of the Athenian allies deserted her in these years. Finally, what was left of the Athenian fleet was destroyed in the harbor of Aegospotami, near where Istanbul is now. The Athenians sued for peace and tore down their own walls and gave their navy to Sparta. Thus ended what was, in my opinion, the true first enlightenment.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home